Dignity Takings | Dignity Restoration

2016 Chicago-Kent Law Review Live Symposium

Dignity Takings | Dignity Restoration

Symposium Editor

Professor Bernadette Atuahene, IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law

Chicago-Kent College of Law

565 West Adams Street

Chicago, Illinois 60661

Thursday, November 10, 2016

Much of the existing literature on the unconsented taking of property focuses on constitutional takings rather than on the complete opposite side of the takings spectrum, where property is taken by individuals or states, no (or nominal) compensation is paid, and dehumanization or infantilization result.

The concept of a dignity takings provides a vocabulary to describe and analyze the takings that poor and vulnerable populations have routinely been subjected to across the globe and in different historical periods; while the concept of dignity restoration provides a lexicon to discuss attendant remedies necessary and, more importantly, a space to re-imagine their purpose and potential.

The Chicago-Kent Law Review 2016 Live Symposium will extend Chicago-Kent College of Law Professor Bernadette Atuahene’s South African case study presented in We Want What’s Ours by examining instances of dignity takings and dignity restoration in different contexts.

Additional symposium information can be found below:

The symposium is free, and lunch is provided for attendees with advance registration. Registration is now closed, thank you for your interest.

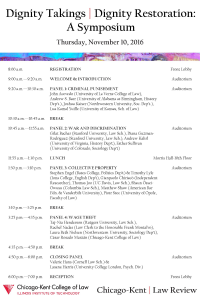

Schedule

| 8:00 a.m. | REGISTRATION | Front Lobby |

| 9:00 a.m.—9:15 a.m. | Welcome & Introduction | Auditorium |

| 9:15 a.m.—10:40 a.m. | Panel 1: Criminal Punishment

John Acevedo, University of La Verne College of Law |

Auditorium |

| 10:40 a.m.—10:55 a.m. | BREAK | |

| 10:55 a.m.—12:05 p.m. | Panel 2: Wage Theft

Taja-Nia Henderson, Rutgers Law School |

|

| 12:05 p.m.—1:35 p.m. | LUNCH | Morris Hall (10th Floor) |

| 1:35 p.m.—2:30 p.m. | Panel 3: War, Disaster, and Discrimination

Gilat Bachar, Stanford Law School |

Auditorium |

| 2:30 p.m.—2:45 p.m. | BREAK | |

| 2:45 p.m.—4:45 p.m. | Panel 4: Collective Property

Stephen Engel, Bates College |

Auditorium |

| 4:45 p.m.—5:00 p.m. | BREAK | |

| 5:00 p.m.—6:00 p.m. | Closing Panel

Valerie Hans, Cornell Law School |

Morris Hall (10th Floor) |

| 6:00 p.m. | Closing and Refreshments | Morris Hall (10th Floor) |

Panel Participants

Panel 1: Criminal Punishment

John Acevedo, Professor of Law, University of La Verne College of Law

Dignity Takings in the Criminal Law of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

This paper examines the issue of when punishment for a crime crosses from being retribution to a dignity taking. From the Norman Conquest until the middle of the eighteenth-century the Common Law of England provided that the property of persons convicted of felonies or treason was forfeited to the crown and their blood corrupted so that their heirs could not inherit; this was in addition to the capital punishment sometimes inflicted upon them. I argue that this is a clear instance of dignity takings. The colonists who traveled to Massachusetts Bay wanted a fresh start and so sought to create a model society based on biblical law as an example of reform for England.

Using over 6,000 criminal cases from the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1630 to 1688 this paper argues that a different form of dignity takings ensued. The use of “scarlet letters,” pillorying, whipping, and other public displays of punishment were all designed to single out unworthy members of the community. I push Atuahene’s concept of dignity takings by offering a sub-category of dignity abuse where rather than taking or destroying their real and personal property the state seeks to destroy their bodies.

Andrew S. Baer, Assistant Professor, University of Alabama at Birmingham

Dignity Restoration and the Chicago Police Torture Reparations Ordinance

A recent municipal ordinance giving reparations to survivors of police torture in Chicago represents an unprecedented effort by a city government to repair damage wrought by decades of police violence. Between 1972 and 1991, a group of white detectives working under the supervision of Commander Jon Burge tortured confessions from at least 118 black criminal suspects on the city’s South and West Sides. Responding to the needs of affected communities, a coalition of torture survivors, their families, civil rights attorneys, and community activists directed a sustained social movement to push the reparations bill through the City Council on May 6, 2015. Representing the holistic approach favored by activists, the $5 million reparations package awarded each of approximately 60 claimants $100,000 in financial payments; privileged access to psychological counseling, healthcare, and vocational training; as well as tuition-free enrollment in City Colleges for themselves, their children, and grandchildren. The ordinance also required the City offer an apology, erect a public memorial, create a community center to provide services for victims of police violence, and develop a public school curriculum to teach the Burge scandal to 8th– and 10th-grade students.

Applying concepts developed by Bernadette Atuahene, I argue that the Chicago police torture cases represent a dignity taking designed to dehumanize and infantilize local black people. I also argue that the 2015 reparations ordinance offers a promising new precedent for dignity restoration in cases of police violence in the United States. According to Atuahene, “dignity restoration is based on principles of restorative justice and thus seeks to rehabilitate the dispossessed and reintegrate them into the fabric of society through an emphasis on process” (We Want What’s Ours, 4). Despite limitations of scope and scale, Chicago’s reparations ordinance models ways to include survivors of police violence in the process of repair, commemoration, and education.

Joshua Kaiser, Law and Social Science Fellow, Northwestern University

Making the Underclass: Deprivation, Degradation, and America’s Hidden Penal Regime

Over the last century, the United States has constructed a vast regime of hidden sentences: punishments imposed by law as a direct result of criminalization, but not as part of the formally recognized, judge-issued sentence. Hidden sentences include restrictions on voting rights, public and private employment, governmental benefits, and other rights. Today, there are more than 35,000 hidden sentence laws across the nation that directly impact about one in four American adults. Yet, this penal regime is hidden: policymakers, scholars, lawyers, judges, and even criminalized people themselves are largely unaware that such punishments exist.

This article argues that hidden sentences are dignity takings that create second-class American citizenship. First, I extend Atuahene’s concept of dignity takings to account for denial of access to property and opportunities to acquire it. Thus, hidden sentences that ban criminalized people from public housing, governmental programs, and employment can be dignity takings to the same extent as those that impose fines and forfeitures. Second, I argue that while many of these punishments are arguably dehumanizing and infantilizing, their hiddenness itself makes them all by definition dignity takings. The presumptions that criminalized people do not even deserve notice of their punishments and that courts have no need to consider or care about this lifelong process of criminalization are themselves key symbols that criminalized people are viewed as the undeserving, irresponsible, vile, and base.

Lua Kamal Yuille, Associate Professor of Law, University of Kansas School of Law

Dignity Takings in Gangland’s Suburban Frontier

This paper will engage Bernadette Atuahene’s dignity takings framework in the context of contemporary American street gangs (e.g. Crips, Bloods, Latin Kings, etc.). Contrary to most popular accounts, it starts with a reimagined and complicated notion of street gangs that emphasizes not their secondary or tertiary violence and criminality but their primary function as corporate institutions engaged in the sustained, transgressive creation of alternative markets for the creation of the types of property interests that scholars have associated with the development and pursuit of identity and “personhood.” From this perspective, the paper applies the dignity takings analysis to public nuisance abatement actions (commonly known as gang injunctions), which have become standard tools in the national gang strategy. These civil mechanisms enjoin the conduct and activities of the gangs, as unincorporated entities, and prohibit named individuals (including but not limited to known and suspected gang members) from engaging in a panoply of otherwise legal activities: displaying gang symbols, wearing clothing or colors associated with a gang, possessing tools or objects capable of defacing real or personal property (e.g. pens), appearing in public view with a known gang member. Through qualitative analyses of interviews, court documents, and political hearings, the paper demonstrates that the dispossession of identity property associated with suburban gang injunctions depresses self- esteem, erodes self-confidence, damages identity and feelings of community worth, and dehumanizes enjoined individuals in a way that deprives them of their fundamental right of dignity, constituting a clear example of a dignity taking.

Panel 2: Wage Theft

Taja-Nia Henderson, Professor of Law, Rutgers Law School

Dignity Takings and Dignity Restoration Examined through the Lens of American Chattel Slavery

This paper grapples with the broader applicability of Bernadette Atuahene’s “dignity takings” theory outside the South African context. Atuahene argues that such takings occur “when a state directly or indirectly destroys or confiscates property rights from owners or occupiers whom it deems to be sub persons without paying just compensation of without a legitimate public purpose.” (We Want What’s Ours, 3) This essay takes up the challenge posed by Atuahene at the end of Chapter 1 to “explore whether the concept of dignity takings helps us to better understand” property atrocities in the US, namely, the systematic dispossession of black property rights under chattel slavery and Jim Crow in the US. In this case study, I argue that the remedial reparations inhering in “dignity restoration” require, at base, political will. When such will is absent, or when the dispossessed remain a political or economic underclass, compensation has limited capacity to restore stolen dignity.

Rachel Nadas, Law Clerk to the Honorable Frank Montalvo, U.S. District Court, Western District of Texas

Throwaway Lives: Dignity Takings and Foreign-Born Workers in the United States

In this article, I intend to apply the theoretical framework of dignity takings and dignity restoration to the epidemic of occupational injuries and fatalities among foreign-born workers in the United States. Specifically, I will be relying upon data gleaned from 85 qualitative interviews that I conducted with immigrant day laborers in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. These interviews focused on the workers’ personal background, experience with workplace risks, injuries, and illnesses, and familiarity with relevant legal protections.

The paper will position these workplace injuries as a quintessential dignity taking, consistent with Professor Atuahene’s framework. At each stage in the analysis, however, this case study presents intriguing theoretical questions. First, the paper will explore the role of the state in contributing, indirectly, to the property deprivation. The role and responsibility of the state can be gleaned from agency (in)action on workplace safety matters, and from how laws have positioned noncitizens in the U.S. legal system at large. Second, the property deprivation itself presents historical and practical questions relating to how the human body has been commoditized in the workplace setting, and in particular, in the context of workplace injuries. Third, the article will explore how foreign-born workers are treated as more expendable or subhuman in both legal and social discourses. Specifically, considerations of race, class, and immigration status align to diminish the value attached to immigrant worker lives.

Having detailed how dignity takings operate in this context, the article will explore possible models of dignity restoration for foreign-born workers who experience occupational injuries. These include significant reforms to prevention efforts and adjudication/enforcement processes, allowing the workers to assume a more active and central role. These reforms are intended to affirm the value of immigrant worker lives and underscore the workers’ humanity, while also reshaping societal perceptions of this segment of the workforce.

Laura Beth Nielsen, Professor of Sociology, Northwestern University

César Rosado Marzán, Associate Professor of Law, IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law

Dignity Takings and “Wage Theft”

This paper brings together Atuahene’s concept of “dignity takings” and labor and employment law (“labor law”). It presents original research compiled through interviews and participant observation on how immigrant, low-wage workers are denied their humanity by employers who (1) treat them as commodities and (2) refuse to pay them– what labor activists call “wage theft.” Since more than a century ago, labor law has been concerned with protecting workers’ dignity, understood to be taken away by employers who treat labor as a commodity. When treated like commodities, workers are denied agency and their human condition. At best, when provided some level of protection by employers, workers are treated paternalistically, as children. When employers refuse to pay workers for their work, workers condition in the labor market begins to resemble compulsory labor, doubly threatening their human dignity.

In this light, labor law understands that workers’ and society’s moral interests lie at stake when labor markets lie unfettered. While labor law generally provides for compensatory damages to workers who suffer wage theft, the concept of “dignity takings” helps to compensate workers for their additional dignity losses. In this fashion, labor law helps to extend “dignity takings” considering the role of commodification, while the concept provides labor law with better remedies to make workers whole.

Panel 3: War, Disaster, and Discrimination

Gilat Bachar, J.S.D. Candidate, Stanford Law School

Access Denied: Barriers to Seeking Civil Justice as a Form of Dignity Taking: Lessons from the Israeli-Palestinian Experience

The injuring state in armed conflict settings typically does not allow civilian victims on the other side to access its domestic courts in order to seek redress for their injuries. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict presents a rare exception to this rule. A unique mechanism enables Palestinian residents of the West Bank and Gaza Strip to bring claims for damages against the State of Israel before Israeli civil courts. These proceedings might be viewed as a mechanism for dignity restoration, one that both provides a remedy when appropriate and recognizes the individual Palestinian’s equal human worth and autonomy. This research seeks to empirically evaluate this assertion. Using data from content analysis of Israeli civil courts decisions over the last two decades, alongside interviews with relevant stakeholders, the study argues that despite this mechanism’s potential to restore the dignity of Palestinian civilians who suffered bodily injuries and property damages as a result of Israeli military actions, it in fact aggravates the harm they sustained. Not only does the study expand the original dignity taking/ restoration framework to an amidst-conflict, under-occupation setting, it also proposes a new way to think of the denial of access to civil justice; as another form of dignity taking.

Diana Guzmán-Rodríguez, J.S.D. Candidate, Stanford Law School

Dignity Takings and Dignity Restoration: A Case Study of the Colombian Land Restitution Program

The Colombian Land Restitution Program, created by the Victims’ Law of 2011, aims to restitute the dispossessed lands to millions of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) who were forced to abandon their possessions as they fled the violence of the internal armed conflict. At the same time, it aims to contribute to the transformation of deep inequalities associated with massive forced displacement. This paper assesses to what extent the socio-legal concepts of dignity takings and dignity restoration can contribute to understanding the forced displacement and land dispossession in Colombia, as well as to enhance the land restitution process. The complexities of both land dispossession and land restitution as well as the persistence of the violence associated with the internal armed conflict create an interesting setting to analyze the appropriateness of these concepts.

This case study relies on two main methods. First, a content analysis of judicial rulings issued as part of the program between the beginnings of its implementation in 2012 and June 2014. Secondly, semi-structured interviews with land restitution judges and beneficiaries of the program. The paper argues that although the Colombian case does not meet all the elements of the dignity takings definition, dehumanization accounts for some of the forms of land dispossession occurred in Colombia. Furthermore, it suggests that the concept of dignity restoration can play a significant role in transitional contexts beyond those defined as dignity takings.

Andrew Kahrl, Associate Professor, University of Virginia

Dispossession via Taxation: Tax Delinquency and African American Land Loss in the Coastal South

This paper examines the role of property tax delinquency laws and administrative practices in the meteoric rise of real estate values and equally dramatic decline of African American landownership along southern coastlines in the 1960s and 1970s. Rising property assessments forced many black landowners to sell under duress and, invariably, at far below market value. Of greater significance, though, was the ease with which unscrupulous speculators were able to manipulate the laws on property tax delinquency to seize valuable property from unsuspecting landowners—and unwilling sellers—for pennies on the dollar.

These unethical, but perfectly legal, strategies not only transformed areas like the South Carolina Sea Islands from a cradle of black landownership into a playground for the rich; it also resulted in the wholesale loss of one of the chief sources of potential wealth—land—that black Americans had in their possession when they emerged from a century of Jim Crow. It’s a history of theft and betrayal that remains as invisible to the throngs of middle- and upper-class Americans—white and black—who flock to the South Carolina and Georgia coasts to vacation in luxury hotels and timeshare resorts as it is seared into the collective memory of black Sea Islanders.

Esther Sullivan, Assistant Professor, University of Colorado Denver

Panel 4: Collective Property

Stephen Engel, Associate Professor, Bates College

Timothy Lyle, Assistant Professor of English, Iona College

Bathhouse Closures as Dignity Takings and Obergefell as Dignity Restoration

When Justice Kennedy announced the ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), which declared state bans on same-sex marriage unconstitutional, he used the word dignity no less than fifty times. The decision, like the United States v. Windsor (2013) ruling, which declared part of the Defense of Marriage Act unconstitutional, and Lawrence v. Texas (2003), which de-criminalized consensual same-sex sexual relations, utilizes dignity as a rhetorical and substantive foundation. Dissenters and supporters of these rulings critiqued them for straying from principled jurisprudence of equal protection or due process; the rulings yielded uplifting but constitutionally garbled claims. Nevertheless, they deserve critical attention that examines more than whether they conform to doctrinal development. Notably, they also reveal what, in a different context, Bernadette Atuahene names “dignity restoration.” Such restoration “compensates” for a prior “dignity taking”—when the state deliberately destroys the rights of those deemed as unworthy of legal protection or even acknowledgment.

Specifically, this paper explores how the closing of gay bathhouses during the height of the AIDS crisis is one such dignity taking, one that did substantial cultural and political work to render gay men culpable for their own community’s sudden and relentless demise. It ultimately perpetuated a narrative of culpability, ignited intense divisions within gay and lesbian communities, and produced within gay men a deep distrust and/or fear of institutions and of one another. While Kennedy’s rulings may be seen as dignity restorative measures, these efforts fail to compensate for the takings suffered by the closing of bathhouses or even by the lack of governmental recognition of the AIDS crisis during the Reagan administration. When these communal spaces were challenged, the logics on which they were premised – gay liberation, the political imperatives of open and public sexuality, and exploration of new and distinct ways of interpersonal connection – were denied and denigrated. Insofar as Kennedy’s rulings premise dignity upon the state’s reinforcement of heteronormative couplings, they deny the aims of liberation and fail to acknowledge the value of liberation’s radical critique.

Gianpaolo Chiriacò, Independent Researcher

Sound Recordings and Dignity Taking. Reflections on the Racialization of Migrants in Contemporary Italy

In the field of ethnomusicology, a discussion around the notion of dignity takings and dignity restoration can provide a fruitful platform to evaluate both our understanding of the cultural values of sounds and the effective results of several projects that have been undertaken under the umbrella of “applied ethnomusicology.” Projects of this kind generally follow the rule of restitution, that is to say that sound recordings made “in the field” and generally archived in big universities or national libraries are now returned to the communities where they have been recorded. In some cases, this phenomenon takes the form of “sound repatriation” (Nannyonga and Weintraug 2012), a term that emphasizes the value of music and dance in the postcolonial nation-building process, in other cases the worldwideweb is the arena that provides the space for restitution (e.g. http://www.culturalequity.org), on the assumption that an online portal is the most democratic form of giving back. Such attempts – as valuable as they are – also raised many questions. I want to focus here on one problematic aspect: sound recordings that are returned often carry – after years in the hands of scholars – meanings and values that are different from, if not opposite to, meanings and values expressed by the people that have been recorded.

Drawing from two case studies of my own research, I will explore the vocal sounds I have been recording and the agency of people I have recorded through the framework of dignity takings and dignity restoration. A vocalist from Senegal performing a piece on the illegal journey through the Mediterranean Sea and a black vendor on the Southern beach of Apulia (Italy) who uses the voice to catch the attention of summer tourists (http://www.afrovocality.com/contemporary-calls/) provided sound recordings that I used for scholarly articles, videos and installations. Their voices, therefore, have been incorporated in theorizations that delineate my interpretation of their role and practices as people of African origins in contemporary Italy, but do not necessarily represent their values and meanings. I will give my two “informers” the possibility to articulate whether or not my work caused any dehumanization or infantilization for them or for people of African descent in a Country in which migrants and refugees are often racialized in media and public discourse (Silverstein 2005), misrepresented, and rarely allowed to speak for themselves. I will also give them the possibility to reflect on what can be done in order to mitigate the effects of dignity taking in my work and whether or not anything can be done to restore their dignity. My aim is to provide a model for ethnomusicologists to reflect on their own projects and fieldworks, to move towards methodologies that can be dignifying for every subject involved in the ethnographic work.

Thomas Joo, Martin Luther King Jr. Professor of Law, University of California, Davis, School of Law

“A Larger Strategy”? Dignity Takings, Urban Renewal, and Sacramento’s Lost Japantown

I propose to apply the concept of dignity takings to urban renewal in Sacramento, California, in the 1950s. Like many other cities of that era, Sacramento used eminent domain to make way for federally subsidized private redevelopment of inner-city neighborhoods. Urban renewal tended to displace poor people and people of color, leading James Baldwin to famously deride it as “Negro Removal.” In Sacramento, Japanese Americans were the most obviously identifiable group impacted by urban renewal. The city’s first urban renewal project razed the city’s Japantown. Japanese American residents and business owners had only recently returned from an even more devastating relocation—to domestic concentration camps during World War II.

In 1954, Sacramento’s City Council and its Redevelopment Agency held hearings on the plan to destroy the neighborhood. A well-organized community sent representatives to testify in opposition, to no avail. For my paper, I will review the hearing transcripts, urban renewal planning documents, and other records in Sacramento’s city archives, as well as contemporaneous newspaper coverage. Unlike the South Africans in Atuahene’s original case study, Japanese American property owners received compensation through the same orderly legal process as others. Furthermore, compared to nonwhites in South Africa, state subordination of Japanese Americans was far less blatant. Express statements of racist motivation seem to be absent. The most obvious program of dehumanization—the internment—had ended. But the takings took place against a background of significant anti-Japanese sentiment, as expressed in immigration restrictions, racially restrictive covenants and even racial violence.

A key aspect of dignity takings is their place in “a larger strategy of dehumanization.” This case study will help test and refine the notion of a “larger strategy” and how to establish a sufficient relationship of takings to such a strategy.

Shaun Ossei-Owusu, Academic Fellow, Columbia Law School

The Good State Giveth and Taketh Away: Race, Class, and Urban Hospital Closings

In the past forty years, health care restructuring and privatization has led to the shuttering of large safety-net hospitals in American cities (e.g. Philadelphia, New Orleans, Washington D.C.). This paper applies concepts in Bernadette Atuahene’s We Want What’s Ours to King/Drew Medical Center – a major hospital and medical school in South Los Angeles that served African Americans and Latinos. The federal government closed the hospital in 2007 and it reopened in 2015. The essay argues that Atuahene’s notions of dignity takings and restoration offer instructive insights into heath care restructuring, particularly in medically unserved communities. At the same time, it also argues that the health care environment for the medically indigent can also help complement and complicate the concepts in We Want Whats Ours, while offering guidance on how to think about the relationship between race, poverty, property, and health care services.

Matthew Shaw, Assistant Professor of Law, Vanderbilt Law School

Creating the Urban Educational Desert through School Closures and Dignity Taking

Closures of urban open-enrollment neighborhood schools that primarily serve students of color are intensely controversial. Districts seeking to economize often justify closures by pointing to population shifts in historically densely populated urban areas. They argue that net reductions in a neighborhood’s school-aged population result in underutilized schools, which do a disservice to students at higher cost to districts. Students and their families and communities counter, pointing to histories of district neglect of their schools and recent school expansions in more affluent neighborhoods of similar population density as belying district claims of utility-based downsizing.

In this paper, I take community beliefs as a serious frame for understanding neighborhood school closures as a property taking (cf. Garnett, 2014). Through qualitative analyses of interviews, court documents, and school-closure hearings in four urban districts, I show that communities interpret district actions as an abandonment of district obligations to educate their children. I further show that affected communities feel openly disregarded at public closure hearings, which they attribute to district devaluing of their children. I argue that closing schools in this manner compounds the physical property loss with a “dignity taking” (Atuahene, 2014) that leaves an “educational desert” in its aftermath, with implications for educational outcomes, student affect and engagement, community support, and institutional legitimacy.

Piotr Stec, Professor Extraordinarius, University of Opole

Dignity Takings Under Communist Rule In Poland

The paper will deal with dignity takings in Poland under communist rule and attempted dignity restorations after 1989. At the end of the WWII Poland’s complicated history became even more complicated. Poles who had survived five years of Nazi occupation suddenly found themselves ruled by another totalitarian system. Transformation of Poland into a communist state required creation of a new social system and eradication of all vestiges of the old one. In this brave new world all means of production were to be owned by the state, there would be only one political party and all needs of the people would be fulfilled by the state.

In my paper I will show how an attempt to create a perfect world led to dignity takings not only from people considered “class enemies,” but also potential beneficiaries of the system. I am going to start with takings of property without compensation which affected not only capitalists and rich landowners, but also charities, small businesses, religious communities and independent farmers. Then I will deal with takings aimed at denigration and humiliation of class enemies, starting from slave labor of so called “miners-soldiers,” through limited access to education, up to policy measures aimed at pauperization of trades and professions traditionally connected with wrong type of people. Next I will discuss measures aimed at limitation of freedom of expression, using the crime of “whispered propaganda” (i.e. gossiping) as an example. I will try to show, that side effect of those measures was infantilization of workers, who were supposed to be beneficiaries of the change.

Finally I will deal with ways the society tried (sometimes successfully) to resist these takings and attempts of dignity restorations after 1989. I will try to show that this resistance against takings and clemency granted to people responsible for enforcement of the takings facilitated peaceful transition but for a price of leaving some of the takings unrestored.

Closing Panel

Valerie Hans, Professor of Law, Cornell Law School

Lasana Harris, Senior Lecturer, University College London