Threat of Wildfire Prompts California Utility Companies to Cut Power to Customers

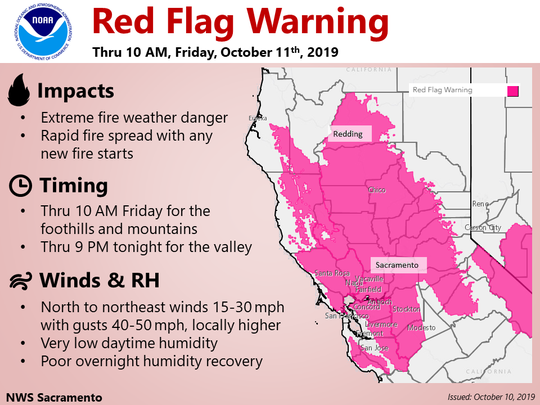

On Wednesday, October 9, Pacific Gas & Electric Company (PG&E) began shutting off power to nearly 800,000 customers in northern California. PG&E stated that the outages were necessary to preempt the risk of wildfires brought on by severe weather conditions like high winds and hot, dry air throughout the company’s service area.[1] At the time PG&E initiated the outages, the company anticipated that some customers could be without power for days.[2]

Southern California Edison Company (SCE), the largest utility provider in south-central California, including Los Angeles County, announced on Thursday, October 10, that it would start cutting power to customers in light of the hazardous conditions caused by the Santa Ana winds.[3] The same day, wildfires broke out in SCE’s service area in Riverside County, east of Los Angeles.[4] SCE anticipates that over 200,00 customers may be affected by the power outages.[5]

These controlled blackouts, also known as “preemptive de-energizations,” are the foundation of PG&E and SCE’s Public Safety Power Shut-off programs (PSPS), which are part of a comprehensive effort to reduce the risk of electrical infrastructure sparking fires. This is accomplished by temporarily turning off power to specific areas.[6] Following the wildfires that devastated parts of California in 2017 and 2018, the California PUC ordered electric utility companies to submit Wildfire Mitigation Plans[7] and this past summer, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed a law that provides $21.5 billion in funding to help utilities pay for wildfire damage, and make upgrades to the electric infrastructure.[8] The California State Legislature, the California Public Utilities Commission (California PUC), and electric utility companies have, in turn, intensified their efforts to improve the safety of electric infrastructure as the threat of seasonal wildfires is exacerbated by changing climate. Dangerous weather conditions have started to subside, though line inspections may delay power returning to some PG&E customers for up to five days[9] and the fires in Riverside County continue to burn.[10]

Featured Image: National Weather Service Sacramento

[1] See Press Release, PG&E Begins to Proactively Turn Off Power for Safety to Nearly 800,000 Customers Across Northern and Central California, Pacific Gas & Electric Company (Oct. 9, 2019), https://www.pge.com/en/about/newsroom/newsdetails/index.page?title=20191009_pge_begins_to_proactively_turn_off_power_for_safety_to_nearly_800000_customers_across_northern_and_central_california (last visited Oct. 9, 2019).

[2] Id.

[3] See Press Release, , Santa Ana Winds Prompt SCE Public Safety Power Shutoffs in Some Southland Areas, Southern California Edison Company (Oct. 10, 2019), https://energized.edison.com/stories/santa-ana-winds-prompt-sce-public-safety-power-shutoffs-in-some-southland-areas.

[4] See Joseph Serna, Hannah Fry, & Alejandra Reyes-Velarde, Numerous Riverside County homes destroyed by fire; SoCal Edison cuts power to thousands, The Los Angeles Times (Oct. 10, 2019), https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2019-10-10/l-a-faces-critical-fire-danger-possible-power-outages-as-santa-ana-winds-buffet-southern-california (last visited Oct. 10, 2019).

[5] See Public Safety Power Shutoffs, Current Status, Southern California Edison Co (effective Oct. 11, 2019), https://www.scemaintenance.com/content/sce-maintenance/en/psps.html (last visited Oct. 11, 2019).

[6] See Rulemaking 18-12-005, Decision Adopting De-Energization (Public Safety Power Shutoff) Guidelines (Phase I Guidelines), California PUC, p. 3 (issued May 30, 2019).

[7] See Rulemaking 18-10-007, Order Instituting Rulemaking to Implement Electric Utility Wildfire Mitigation Plans Pursuant to Senate Bill 901 (2018), California PUC (issued Oct. 25, 2018).

[8] See Alejandro Lazo & Katherine Blunt, California Legislature Approves Multibillion-Dollar Wildfire Fund, The Wall Street Journal (July 11, 2019), https://www.wsj.com/articles/california-legislature-approves-multibillion-dollar-wildfire-fund-11562870591 (last visited Oct. 11, 2019).

[9] See Thomas Fuller, Californians Confront a Blackout Induced to Prevent Blazes, The New York Times (Oct. 10, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/10/us/pge-outage.html (last visited Oct. 11, 2019).

[10] Incident Overview, California Department of Fire & Forestry Protection, https://www.fire.ca.gov/incidents/ (last visited Oct. 11, 2019).