Trump Too Small: Does Political Speech Trump Trademarks?

Written by Grace Wickstrom

Criticizing political figures sits at the bedrock of the First Amendment right to free speech under the U.S. Constitution.[1] When you imagine a challenger of this right, you likely do not envision the United States Patent and Trademark Office as the alleged perpetrator. Nevertheless, this was Steve Elster’s (“Elster”) claim on appeal to the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals. Following the denial of his application for the mark TRUMP TOO SMALL, the court ruled in favor of Elster and his claim that Section 2(c) of the Lanham was unconstitutional as applied. Now, the Supreme Court must once again address the stark tension between the First Amendment and Trademark law.[2] Specifically, the distinctions between viewing Section 2 provisions of the Lanham Act through a constitutional or doctrinal trademark lens.

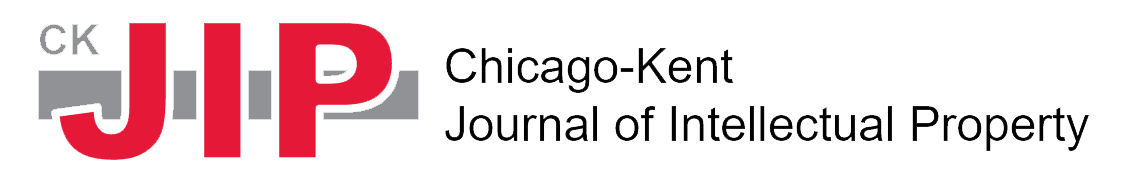

After Florida Senator Marco Rubio publicly mocked the size of former President Donald J. Trump’s hands during a debate, the joke followed Trump throughout the 2016 presidential primaries into his presidency.[3] While American popular culture turned the jape into a prevalent meme, Elster filed a federal trademark application for the mark TRUMP TOO SMALL for shirts and other wearable garments.[4] Elster’s mark capitalized on the sentiment of Trump’s “hands” being below average size to criticize the former president’s policies.[5] While the reader may find this mark entertaining, the Trademark Office was not as amused—rejecting the application under Section 2(c) of the Lanham Act, which [6] Elster Appealed.

Figure 1. Photograph of Elster’s Shirts on trumptoosmall.com (2023), https://trumptoosmall.com/.

Reversing the PTO’s rejection on February 22, 2022, the Court of Appeals of the Federal Circuit held Section 2(c) as applied to the mark TRUMP TOO SMALL unreasonably burdened Ester’s First Amendment rights.[7] While the Federal Circuit Court determined the Supreme Court’s previous Trademark/First Amendment decisions do not resolve the constitutionality of Section 2(c), the cases do create a foundation for the Federal Circuit court’s analysis.[8]

Matal v. Tam and Lancu v. Brunetti: The History of Section 2 Challenges

Elster’s challenge to Section 2(c) does not start on a clean slate. The Supreme Court has addressed various components of 2(c)’s neighbor, 2(a), in previous decisions. The Court’s reasoning and holdings in Matal v. Tam (“Tam”) and Lancu v. Brunetti (“Bruntetti”) serve as guideposts for determining the constitutionality of Section 2 provisions concerning the First Amendment. More importantly, this case linage shows the incremental breakdown in the Court’s reasoning originating in Tam.

In Tam, an Asian American band sought a federal trademark registration in THE SLANTS.[9] The PTO denied the registration under Section 2(a), which bars the registration of a mark that contains “matter which may disparage … persons, living or dead, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols, or bring them into contempt, or disrepute.”[10] However, the registrants claimed their use of the slur was not disparaging but empowering as they sought to ‘reclaim’ the term and “drain its denigrating force.”[11] After the registrants appealed the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) decision to affirm the refusal, the Federal Circuit found the Disparagement Clause facially unconstitutional under the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.[12] The Supreme Court granted Certiorari.

Figure 2. Photograph of The Slants “Pageantry” album cover in Pageantry, The Slants,

https://theslants.com/album/1920849/pageantry (last visited Nov. 20, 2023).

Affirming the Circuit Court, Justice Alito delivered the Supreme Court’s opinion. While unregistered marks may still be used in commerce and may be enforced as state common law rights or under the Lanham Act itself, Alito highlighted the legal rights and benefits only conferred upon federally registered trademark holders.[13] Additionally, the Court rejected the government’s contentions that trademarks are government speech;[14] a form of government subsidy;[15] or that the Disparagement Clause falls within the “government program” doctrine.[16] The Court determined that denying registration to marks that offend a group under the disparagement clause is viewpoint discrimination because “giving offense is a viewpoint.”[17]

Concluding government speech and subsidy arguments cannot uphold the Section 2(a) disparagement clause, the question turned to whether trademarks are considered commercial speech subject to relaxed scrutiny.[18] Central Hudson outlines the factors of commercial speech.[19] However, the Court left this question open, and instead held that the disparagement clause cannot survive Central Hudson review where the clause was not narrowly tailored to a substantial government interest. [20] The disparagement clause served as a “happy-talk clause” and went further than serving the proposed government interest in protecting the orderly flow of commerce. [21] Therefore, the Lanham Act’s Section 2(a) disparagement Clause violated the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment. [22]

The Supreme Court again confronted Section 2(a) in Brunetti when the PTO denied registration to the mark FUCT under Section 2(a)’s “immoral or scandalous” clause. [23] Relying on Tam, the Court agreed that if the “immoral or scandalous” bar constituted viewpoint discrimination, it “collides with First Amendment doctrine.”[24] Writing the opinion of the Court, Justice Kagan analyzed dictionary definitions of “immoral” and “scandalous” to conclude that the registration bar was facially viewpoint biased towards viewpoint that did not align with “conventional moral standards.”[25]

Figure 3. Photograph of FUCT label in fuct, https://fuct.com/ (last visited Nov. 20, 2023).

Unlike Tam, The Brunetti court was not a landslide victory for the registrant. As the realities of applying the Tam decision to other provisions of Section 2 set in, a few justices pushed back on the established doctrine.

Justice Sotomayor was quick to point out the repercussions of the majority opinion: the government cannot refuse to register “the most vulvar, profane, or obscene words and images imaginable.”[26] Instead of reading “immoral” and “scandalous” as a unified standard, Sotomayor proposes another reasonable statutory interpretation. “Scandalous” should be read as a separate feature barring the registration of “offensive modes of expression.”[27] Therefore, a bar on “immoral marks”—transgressions of social norms—is viewpoint based and unconstitutional, but the trademark registration system may reasonably restrict viewpoint neutral modes of expression as a form of content discrimination.[28] Without clearly establishing what framework of government speech the trademark regime falls into, Sotomayor suggests “reasonable, viewpoint-neutral content discrimination is generally permissible.”[29] Trademark registration can rely on these “viewpoint-neutral content regulations” because the PTO is not restricting the applicant from using his mark sans registration, the PTO only denies him “ancillary benefits.”[30]

Justice Breyer moves even further away from the Court’s decision in Tam in his concurrence. Breyer expresses doubt in the effectiveness of the category-based approach adopted in Tam; “The First Amendment is not the Tax Code.”[31] Walking through an analysis of why trademark law does not squarely fit in commercial or government speech and the muddy line between viewpoint and content-based discrimination, Breyer ultimately concludes the Court should move away from its rigid First Amendment categories.[32] Why shove a square block in a round hole? Especially if the results strike down reasonable regulations and restrictions in our trademark regime[33] . Instead, Breyer urges the Court to utilize the categories as “rules of thumbs” while balancing the proportionality of regulation’s speech-related harm to the “relevant regulatory objectives.”[34] Utilizing his balancing approach, Breyer embraces Justice Sotomayor’s narrow interpretation of Section 2(a). He concludes that the government’s interest in disincentivizing the use of vulgar language in commerce and protecting the “sensibilities of children” outweighs the potential First Amendment harm of prohibiting “scandalous” marks.[35] While his final analysis may stray from the true objectives of the trademark system, the Elster Court may want to take a feather from Breyer’s hat as they prepare their upcoming decisions.

In re Elster:

In In re Elster (“Elster”), the Federal Circuit Court relied on Tam and Brunetti’s holding to establish that Trademarks are private, not government speech, and are therefore entitled to some form of First Amendment protection.[36] Even though the denial of registration is not an absolute prohibition on the applicant’s speech, the court recognized registration denial disfavors the speech being regulated.[37] The court also reasoned content-based restrictions in trademark registration are not as suspect as viewpoint-based restrictions.[38] Still, there must be substantial government interest in the restriction even if viewpoint-neutral content-based restrictions are not subjected to strict scrutiny.[39]

Finding Elster’s First Amendment right to criticize political figures undeniably substantial, the court struggles to find any of the substantial interests proposed by the government to outweigh the First Amendment harm of Section 2(c)’s restriction.[40] The government argued that privacy and publicity grounds served as the government’s interest in barring registrations under 2(c).[41] However, The court found Trump, as a public figure, does not enjoy a right to privacy absent actual malice.[42] Furthermore, the court reasoned that where there is no misappropriation or plausible suggestion that Trump endorsed the mark, there is no actionable claim to a right of publicity when the speaker seeks to criticize a public official without consent.[43] Ultimately, the circuit court held the PTO’s refusal of Elster’s mark under Section 2(c) unconstitutional as applied.[44] Despite Elster raising an as-applied challenge to 2(c), in dictum, the Court reasoned Section 2(c) is overbroad and potentially facially unconstitutional as a substantial number of its applications may violate free speech. [45] Earlier this year, the Supreme Court granted certiorari to hear the case on June 5, 2023. [46]

While the Federal Circuit Court relied on the holdings of Tam and Brunetti, there are glaring concerns in the overall trajectory of these cases. The Justices are increasingly weary of their initial holding in Tam, especially when applied to other provisions of Section 2. [47] While the Court is months away from releasing opinions on Elster, the oral arguments held on November 1, 2023, shed light on where the Justices’ stand. The overall theme: We should uphold 2(c); tell us how.

[1] State v. Drahota, 788 N.W.2d 796, 805 (Neb., 2010)( “If the First Amendment protects anything, it protects political speech and the right to disagree”).

[2] See generally Matal v. Tam (Tam), 582 U.S. 218 (U.S., 2017); Iancu v. Brunetti (Brunetti), 139 S. Ct. 2294 (U.S., 2019).

[3] Alexandra Jaffe, Donald Trump Has ‘Small Hands,” Marco Rubio Says, NBC News, (Feb. 29, 2016, 4:25 AM), https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2016-election/donald-trump-has-small-hands-marco-rubio-says-n527791.

[4] In re Elster, 26 F.4th 1328, 1330 (C.A.Fed., 2022)

[5] Id.

[6] 15 U.S.C. § 1052(c).

[7] In re Elster, 26 F.4th at 1339

[8] Id. at 1331.

[9] Tam, 582 U.S. at 223

[10] 15 U.S.C. § 1052(a).

[11] Tam, 582 U.S. at 223.

[12] Id.

[13] See Id. at 226. (stating registration on the principal register (1) serves as constructive notice of ownership; (2) is prima facie evidence of mark validity and the owner’s exclusive right to use the mark in commerce; (3) incontestable status may be achieved after five years; and (4) a registered mark owner may stop the importation of infringing products).

[14] See Id. at 234-39 (Stating the government would be babbling and contradicting itself if marks were government speech and trademarks do not have characteristics that are identified in the public mind a government speech, therefore trademarks are private speech.)

[15] See Id. at 239-41 (while the “government is not required to subsidize activities it does not wish to promote” the trademark system is nothing like government subsidy programs since the applicant must pay filing and maintenance fees).

[16] See Id. at 241-44 (Many government program doctrine cases are not relevant, and more analogous cases under the government program doctrine where the government created forums for private speech, viewpoint-based discrimination is forbidden).

[17] Id. at 243.

[18] Id. at 244

[19] See generally, Cent. Hudson Gas & Elec. Corp. v. Public Serv. Comm’n, 447 U.S. 557, 566 (1980) (“whether (1) the speech concerns lawful activity and is not misleading; (2) the asserted government interest is substantial; (3) the regulation directly advances that government interest; and (4) whether the regulation is ‘not more extensive than necessary to serve that interest”’).

[20] Tam, 582 U.S. at 245-46.

[21] Id. at 246-47.

[22] Id.

[23] See Brunetti, 139 S.Ct. at 2298; 15 U.S.C. § 1052(a) (“[c]onsist[ ] of or comprise[ ] immoral[ ] or scandalous matter”).

[24] Id. at 2299.

[25] Id. at 2300.

[26] Id. at 2308 (Sotomayor, J., concurring).

[27] Id.at 2310.

[28] Id. at 2313.

[29] Id. at 2317.

[30] Id. at 2317.

[31] Id. at 2304 (Breyer, J., concurring).

[32] Id. at 2304-06.

[33] Id.at 2304.

[34] Id. at 2306.

[35] Id. at 2306-08.

[36] In re Elster, 26 F.4th at 1331-32 (Discussion in Tam about the differences in other speech that is considered government and the trademark regime).

[37] Id.; See supra note 13 and accompanying text.

[38] See Generally In re Elster, 26 F.4th. at 1331-33.

[39] Id. at 1333-34.

[40] See Generally Id. at 1334-39.

[41] Id. at 1334–35.

[42] Id. at 1335.

[43] Id. at 1336-38.

[44] Id. at 1339.

[45] Id. at 1339.

[46] Vidal v. Elster, 143 S.Ct. 2579 (Mem) (U.S., 2023).

[47] See supra notes 25-34 and accompanying text.