Environmental Deregulatory Landscape in 2019

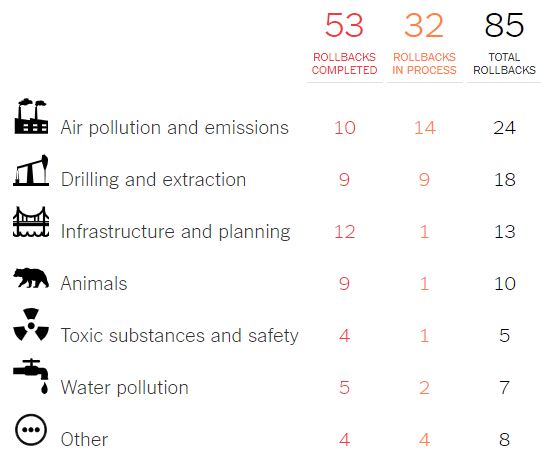

President Trump believes that “an ever-growing maze of regulations, rules, restrictions [sic] has cost our country trillions and trillions of dollars, millions of jobs, countless American factories, and devastated many industries.”[1] He campaigned on the promise to eliminate the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) “in almost every form,” leaving “only tidbits” intact.[2] According to the White House, “President Trump has reduced a historic number of burdensome and unnecessary regulations and stopped the massive growth of new regulations.”[3] The Administration’s environmental deregulatory agenda includes 85 rollbacks in air pollution and emissions standards, drilling and extracting, infrastructure and planning, wildlife protection, toxic substances and safety, and water pollution.[4] In the EPA’s FY 2020 Budget in Brief, the stated mission of the EPA is to “protect human health and the environment,” and according to the EPA, “we can all agree that we want a clean, healthy environment that supports a thriving economy.”[5] The report went on to say, “[e]nvironmental stewardship that supports a growing economy is essential to the American way of life and key to economic success and competitiveness.”[6]

The Administration’s most recent deregulatory success came with abandoning the Obama-era definition of what qualifies as “waters of the United States,” which provided enhanced protections for wetlands and smaller waterways. Under the new Rule, only wetlands “that are adjacent to a major body of water, or ones that are connected to a major waterway by surface water” will be federally protected.[7] The EPA gave four reasons for repealing the 2015 Clean Water Rule: (1) the Rule exceeded the agencies implementing authority based on Justice Kennedy’s significant nexus test in Rapanos;[8] (2) the Rule failed to adequately consider that it is the responsibility and right of the States to protect and “plan the development and use . . . of land and water resources’”; (3) to avoid future unconstitutional land encroachments by the federal government; and (4) the “distance-based limitations” suffer from “procedural errors” and lack “adequate record support.”[9] At a press hearing for the repeal, EPA Administrator, Andrew Wheeler, said that the EPA is “delivering on the president’s regulatory reform agenda,” and the agency is working on 45 more deregulatory actions.[10]

Critics of the Administration’s deregulatory agenda in the EPA have come just short of classifying it as “regulatory capture.”[11] Regulatory capture occurs when agency regulation departs from the public interest, and is directed towards the regulated industry. Although falling short of regulatory capture, critics believe the Administration’s actions show “an ambitious, intensifying movement to cripple the EPA’s capacity to confront polluting industries and promote public and environmental health.”[12] They further contend that the consequences of this deregulatory agenda “will likely fall hardest on vulnerable social groups, such as low-income communities, farmworkers, and first responders.”[13] On the other hand, proponents of the Administrations regulatory reform agenda are celebrating how the “Environmental Protection Agency managed to exceed its deregulatory goal” of removing two rules for every one they proposed.[14]

In addition to deregulation, the EPA has proposed to eliminate 41 current EPA programs and sub-programs while drastically cutting its budget in 2020. The EPA’s FY 2020 Budget in Brief requested $6.068 billion, which “represents a $2.76 billion, or 31 percent reduction from the Agency’s FY 2019 Annualized Continuing Resolution.”[15] The EPA contends that this budget is sufficient to support its “highest priorities” and fulfill its “critical mission for the American people.”[16] Among the programs to be cut are: Environmental Education, Pollution Prevention, Reducing Lead in Drinking Water, Regional Science and Technology and Water Quality Research and Support Grants.[17] While it is unlikely that the proposed budget cuts will be approved by Congress, the FY2020 Budget in Brief signifies a continued departure from the Obama-era expansion of the EPA.

With 85 environmental regulatory rollbacks, a proposed 31 percent reduction in funds, and the elimination of “funding for fourteen voluntary climate-related partnership programs,” President Trump is delivering on his campaign promise to eliminate the EPA “in almost every form.”[18] While the Administration continues to deliver on its promise, according to a 2019 Gallup Poll, “[b]y the widest margin since 2000, more Americans believe environmental protection should take precedence over economic growth when the two goals conflict.”[19] Currently, sixty-five percent of Americans, Republican and Democrat, believe that the environment should take priority over “a thriving economy.”[20]

While President Trump has not managed to eliminate the EPA “in every form,” he has managed to erode many of the environmental law principles which guided the agency for many years. Many States are pushing back against the Administration’s deregulatory agenda and countless lawsuits challenging their actions have been filed.

*Featured Image: 84 Environmental Rules Being Rolled Back Under Trump, The New York Times (Sept. 12, 2019).

[1] President Donald J. Trump’s Historic Deregulatory Actions are Benefiting American Families, Workers, and Businesses The White House, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/president-donald-j-trumps-historic-deregulatory-actions-are-benefiting-american-families-workers-and-businesses/ (last visited Sep 15, 2019).

[2] The Fox News GOP debate transcript, annotated The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/03/03/the-fox-news-gop-debate-transcript-annotated/ (last visited Sep 15, 2019).

[3] The Office of White House, supra, n. 1.

[4] Nadja Popovich, Livia Albeck-Ripka, and Kendra Pierre-Louis, 84 Environmental Rules Being Rolled Back Under Trump, The New York Times (Sept. 12, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/climate/trump-environment-rollbacks.html (last visited Sep 15, 2019) (A New York Times analysis, based on research from Harvard Law School and Columbia Law School).

[5] FY 2020 EPA Budget in Brief, p. 1 (March 2019), https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2019-03/documents/fy-2020-epa-bib.pdf.

[6] Id.

[7] Bill Chappell, EPA Makes Rollback Of Clean Water Rules Official, Repealing 2015 Protections, NPR, https://www.npr.org/2019/09/12/760203456/epa-makes-rollback-of-clean-water-rules-official-repealing-2015-protections (last visited Sep 15, 2019).

[8] Rapanos v. United States, 547 U.S. 715, 126 S.Ct. 2208, 165 L.Ed.2d 159 (2006).

[9] Definition of “Waters of the United States” – Recodification of Pre-Existing Rules (Pre-Publication Version) EPA (Sept. 12, 2019), https://www.epa.gov/wotus-rule/definition-waters-united-states-recodification-pre-existing-rules-pre-publication-version (last visited Sep 15, 2019) (quoting 33 U.S.C. 1251(b)).

[10] Id.

[11] Lindsey Dillon et al., the “EPA Under Siege” Writing Group, The Environmental Protection Agency in the Early Trump Administration: Prelude to Regulatory Capture, NCBI, S90 (2018), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5922212/pdf/AJPH.2018.304360.pdf.

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14]EPA exceeds 2-for-1 deregulation goal set by Trump administration, Federal News Network, (Sept. 3, 2019), https://federalnewsnetwork.com/federal-drive/2019/09/epa-exceeds-2-for-1-deregulation-goal-set-by-trump-administration/ (last visited Sept. 23, 2019).

[15] FY 2020, supra, n. 5 at 1-2.

[16] Id. at 2.

[17] Id. at 89-93.

[18] Id. at 94.

[19] Lydia Saad, Preference for Environment Over Economy Largest Since 2000, Gallup (April 4, 2019) https://news.gallup.com/poll/248243/preference-environment-economy-largest-2000.aspx (“Results for this Gallup poll are based on telephone interviews conducted March 1-10, 2019, with a random sample of 1,039 adults, aged 18 and older, living in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. For results based on the total sample of national adults, the margin of sampling error is ±4 percentage points at the 95% confidence level”) (last visited September 18, 2019).

[20] See FY2020, supra, n. 5.